Islington Mill, James Street, Oldfield Road, Salford

- Contractor David Bellhouse and Son

- Ironwork Bowman Galloway and Company (Observer)

Between 1819 and 1824 six steam powered cotton spinning mills were built in the Oldfield Road district of Salford close to the terminus of the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal. All were dependant on the canal for the supply of both coal and water for their boilers. Of these only Islington Mill of 1823 survives.

In March of 1823, David Bellhouse and Son built a “fire-proof” cotton spinning mill for Nathan Gough. Intended as a room-and-power mill, this was tenanted out to persons involved in cotton spinning. By 1824 the mill was occupied on the ground floor by Mr Buckley, on floors 1 and 2 by Nathan Gough for cotton spinning, on floors 3 and 4 again by Nathan Gough for machinery manufacture, and the 5th floor had been recently occupied by Chadwick and Grimston. An estimated 200, chiefly young people were employed in the building. The mill was 116 feet long and 40 feet 2 inches internal measure on the top floor. It was six storeys high with attic room and divided into twelve bays with an internal beam engine house at the western end (marked by an arched window), with an upright drive shaft to each floor. Floors comprised transverse shallow brick arches between cast iron beams, approximately 20 feet long and weighing about 12 cwt each on which were laid flag floors to level the surface. Initially the floors were supported by a single row of columns only but following the collapse of 1824 their number was doubled. External walls of were of diminishing thickness - four brick wide foundations, three brick thick walls to top of second storey, two and a half brick thick walls to top of fourth storey and two bricks thick to roof. Bays were generally 9 feet wide. However, the western bays were wider, bays 1 and 2 being 11 feet 6 inches in width and bay 3 being 11 feet 9 inches wide. Notwithstanding the increased loads over these bays, the Manchester Guardian believed that no additional allowance had been made in the strength of the beams in this area.

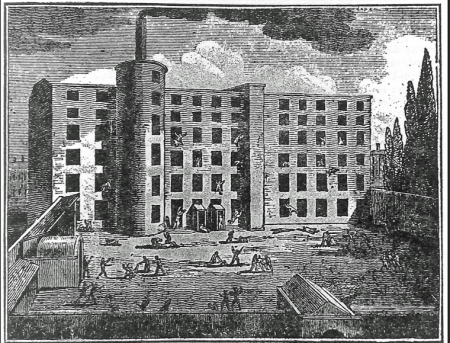

The mill also featured one of the earliest forms of mill chimney in which the stack was combined with the principal stair in a turret with the chimney rising through the centre of a spiral stair. It is this form which is depicted in the 1824 drawing of Islington Mill but is no longer extant. It was originally on the west side of the mill, beside the internal courtyard. This is actually a very strong structure, with the stone steps linking the chimney shaft and the curving outer wall of stair turret giving stability to the lower stages of the chimney. This early form of mill chimney is found in several early cotton mills in Manchester, including the complex of four mills known as Murray's Mills, in Ancoats beside the Rochdale Canal, begun in 1798.

Within twelve months of opening there occurred a catastrophic failure of part of the structure - A DREADFUL ACCIDENT AT MANCHESTER - On Wednesday 13 October 1824 part of Gough’s mill collapsed when a beam at the north-west end of the structure supporting the top floor failed under the weight of the machinery housed there. The weight of the machinery as it fell caused the floors below to give way with the loss of twenty-one lives. The apparent cause of the collapse was a flaw in an iron beam. Gough hinted at negligence. He claimed he had watched most of the iron beams being tested and proved before they were used at the construction site. The testing of the iron beams for the upper floors of the mill occurred while he was sick in bed. Unlike Gough, David Bellhouse junior made no comment to the press at the time. Twenty years later, Bellhouse stated that the flaw in the beam in the Gough mill was apparent only after the accident and not before. Despite the tragedy, the Manchester Guardian commented that, in general, the construction of Gough’s mill was very sound and that the brickwork was very good. When the beam broke, only the arches below it gave out; the outer walls of the building held so that the rest of the building remained intact.

A coroner’s inquest was held at 10.00 am the following day at which time only three witnesses were called and no attempt was made to ascertain the cause of the accident. The Jury then consulted for a short time, and found a verdict to the effect that the deceased persons were killed by the accidental falling in a porting of a cotton-mill, in Salford, the property of Nathan Gough.* It was left to the Manchester Guardian to attempt to piece together details of events. Following the disaster, the mill was restored but with two additional rows of columns introduced to reduce the span of the beams. Further modifications and alterations took place over the next hundred years as included in the listing notice.

About 1816 David Bellhouse was joined in partnership by his son, also named David, (1792-1866). David Bellhouse junior who was described as a joiner and builder living in Faulkner Street. The younger David Bellhouse carried on in the tradition of his father by erecting houses, warehouses, mills and public buildings throughout his career. Within a decade David junior was operating his building business independently of his father and went on to become perhaps the leading Manchester contractor of the mid-Victorian period. The partnership was formally dissolved on December 31, 1824. All other facets of the father’s business related to timber operated under the name of David Bellhouse and Son; the new partnership under the old name was between David Bellhouse senior and his son John. Like his father, David Bellhouse continued the process of vertically integrating his building business. During his father’s lifetime, David Bellhouse junior had access to the raw materials through his father’s timber business and iron foundry. Throughout their careers David Bellhouse senior and junior described themselves as building contractors. As was common at the time they might involve themselves to some degree in the design of the simpler structures such as houses of which they built considerable numbers. However, neither ever claimed to be an architect, nor had they the training to do so. Significantly, The Observer of 18 October notes that the mill was built for Mr. Gough, and under his direction, by Mr Bellhouse (author’s italics). Gough’s evidence at the inquest shows that he had a considerable and detailed knowledge of the construction and may indicate that he bore some responsibility for the design. Given that he was, in part, an inventor and engineer, he undoubtedly had the skill to produce the necessary plans.

* Nathan Gough was not strictly the proprietor of the mill - the machinery and works were Mr. Gough's, but the mill itself belonged to James Bateman. It was, however built for Mr. Gough, and under his direction, by Mr Bellhouse. [Leeds Mercury}

Reference Manchester Guardian Saturday 16 October 1824 page 3

Reference Observer Monday 18 October 1824 page

Reference David R Bellhouse: David Bellhouse and Sons, Manchester. 2001 Ontario, Canada.

Reference British Brick Society Information 113 July 2010 page 2

Reference Obituary: Nathan Gough 1790-1852. Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers Volume 14 1855 page 152

Reference R. McNeil and M. Nevell (2000), A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Manchester.