The Portico Library 57 Mosley Street Manchester

In the late eighteenth century Manchester had a number of libraries ranging from early institutional establishments at Sacred Trinity, Salford, the Collegiate Church and Chetham's Library (all founded before 1700) to various private or specialist societies' collections. These included those of the Botanical Society and the Literary and Philosophical Society. There were also book clubs, and a number of circulating or subscription libraries whose stock ranged from the exclusively non-fiction to a mix including many of the popular novels of the day. Some were in 'upper rooms', others run by booksellers. “Newsrooms” in coffee houses and taverns, provided a range of newspapers, which were heavily taxed and very expensive. The North was particularly prominent in the development of subscription libraries from the mid eighteenth century onwards. This was often influenced by a Nonconformist interest in furthering knowledge and culture. Among the earliest were the Liverpool Library (1758) and those in Birmingham, Warrington and Leeds. The immediate inspiration for the Portico Library and Newsroom came from Liverpool where a committee was raising the money to build the Athenaeum Library and Newsroom, to rival the old Liverpool Library.

In 1796, Michael Ward and Robert Robinson, both members of the Manchester Old Subscription Library, visited Liverpool. They came back to “wonder and lament” that such a large and opulent town as Manchester had no combined newsroom, circulating library and reading room. This would have “the advantage of a library, newsroom and club.” Their first attempt to increase the subscription to the Old Subscription Library and alter the premises failed. However, after one false start and some difficulty, they managed to secure the names of 400 leading Manchester citizens as subscribers to a new institution. These included Nathaniel Heywood of Heywood's Bank, Dr John Ferrier and many other individuals prominent in the development of the town. (Michael Ward Letter - Manchester Gazette 25 January 1808)

The Manchester Library was to be a proprietary subscription library. Each member was a proprietor who paid an initial 13 guineas for his share, followed by an annual subscription of 2 guineas. Similar schemes were employed for institutions as diverse as local hospitals and the Theatre Royal. Subscribers gained a share in the project and privileges of membership, such as the right to nominate occupancy of a hospital bed, or free theatre seats.

The site chosen for the new Library was at the heart of the most fashionable district in Manchester. At the end of the eighteenth century Mosley Street was still at the very edge of the town, an area of wealthy homes and fine churches. The Portico was to be built opposite the fashionable Independent Chapel and the Assembly Rooms (with the new Theatre Royal soon to be built beyond them). It was at the social hub of Manchester in Athe most elegant and refined street in town@according to a Portico Library pamphlet. Nearby were the merchants' houses where many of the members and potential members lived and worked. The land was owned by Peter Marsland, a speculator and cotton manufacturer, who rented it to the Portico for 50.16s 6d annually. The committee had bought the option on the site from the Manchester Billiard Room Society for £240 but in 1810 the Trustees of the Portico bought the freehold from Marsland and his partner, George Duckworth, a local solicitor.

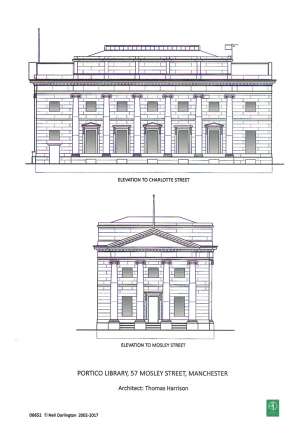

Thomas Harrison was appointed architect in 1802. The foundation stone was laid in 1802 and in July 1803 Nathaniel Heywood signed a contract with David Bellhouse to build the Portico. An impressive parchment document, it lays down the quality of materials to be used and directs Bellhouse to build from Harrison's 'rough plans'.The only Harrison drawings which have survived are the elevation of "The Manchester Library" at the Chester Records Office, together with a longitudinal section, discovered in a Chester antique shop and now in The Portico archives. Both vary in minor details from the final building; but are beautifully drawn in pen and wash. The estimated cost of the building was £5000 and the final amount paid to Bellhouse was £6,881 5s 3d. Harrison's fee for designing the Portico was £250 or 5% of the estimated cost.

The front elevation of the Portico was probably based on the north elevation of the Temple of Minerva in Athens which Harrison is known to have drawn. He was creating one of the earliest neo classical buildings in Britain. The entrance steps between the massive Ionic pillars led past the great staircase (now demolished) to the newsroom which occupied most of the ground floor. Long sash windows down the Charlotte Street side on the ground floor matched square windows above. The library gallery on the first floor ran round the walls and overlooked the room below. At the far end of the newsroom was the committee room, and beside it a back staircase (still extant) giving access from Back George Street to the ground and first floors. The main entrance to the first floor library was by means of the front staircase, where at the top an imposing central door led to the library gallery. At the far end, over the committee room, was the reading room. Although the interior proportions have been destroyed by the insertion of a lay light and later a floor at gallery level, the interior remains one of the best in Manchester. The building is roofed by a saucer dome, an unexpected feature, all but invisible from the outside. Constructed of timber and inset with glazed lights, it is supported by segmental barrel vaults at each end of the building and segmental arches at the sides. Originally, this imposing central space was fully open to the dome above with its glazed centre (but not at that time with with its ornate mid Victorian stained glass panels). Stewart considered that this dome could only be paralleled by the laater works of Sir John Soane

A contemporary description read: The New Library and Newsroom A most elegant edifice of the Ionic order, now building in Mosley Street, of Runcorn stone. It is erected by subscription, for the purpose of containing a public library upon a grand scale, and an elegant Newsroom, which is open only to subscribers, and strangers introduced by them. The entrance to this building is from Mosley Street, by a portico; on the right hand will be the great staircase, leading to the library; and on the left a bar. The Coffee or Newsroom* is lighted from the dome on the top of the building, as well from Charlotte Street, is 65 feet long, and 42 feet wide.** The height to the gallery is 16 feet, and to the top of the dome 44 feet. The library is of the same size as the Newsroom, and will form a gallery overlooking the Newsroom, being open in the centre, and guarded with iron rails. It is building by Mr.Bellhouse, upon a plan, and under the superintendence of Mr. Harrison of Chester, and will cost the subscribers upwards of six thousand pounds. [(Joseph Aston. A Picture of Manchester Manchester 1816 Page 177]

* Tea, Coffee and Soups will be allowed in the Newsroom, but not in any other of the rooms belonging to the institution.

** It is larger by about 700 square feet than the coffee room of the Athenaeum in Liverpool.

The library officially opened in 1806 and on 20 February the committee resolved "the name Portico be given to these rooms." However, the new building was not without its problems. The innovatory central heating system installed by Harrison did not work at first. The fluted cast iron pillars supporting the gallery doubled as radiators and the steam heating apparatus for these was "totally inadequate." Fortunately, open fires in the the reading room provided additional warmth.The thick plaster walls took so long to dry that decorating had to be delayed until June 1808. The colours chosen were white and stone for the walls, pale straw for the doors and bookcases, and white for the other woodwork. A paint scraping taken in 1986 showed over twenty subsequent paint layers, ranging from white to green, to dark red and magenta.

By 1809 the roof was leaking and the committee took Mr. Bellhouse to arbitration when a settlement was agreed and repairs carried out. In March 1813 a Mr. Burton was called in to repair the roof. In May 1822 repairs were again under discussion.

As in the rest of the growing town of Manchester water and sewerage presented difficulties. At first water came from a well in the basement but in 1813 the Stone Pipe Company was brought in to improve the supply. The water closets, another innovation of Harrison's, were a constant trouble. In 1815 the situation was so bad that they were locked up "as all attempts to keep them in order had failed." A new closet was opened in 1818 "with such additions as will do away with every offensive smell."

Peter Ewart, a committee member and experienced engineer, was asked to obtain a wind dial and wall clock. They were provided by Thwaites of London, who had supplied those of the Liverpool Lyceum, at a cost of 80.7s.2d. The task of maintaining the clock was given to the first and most famous honorary member, John Dalton. The committee asked that 'he should see to the going of the clock' and in return offered him honorary membership. The clock is now powered by electricity; the wind dial still goes with the wind.

Lighting at first was by fifteen pairs of candles supplemented later by Grecian style cut glass lamps, at a cost of ,200 (with a discount for cash). Two Portico proprietors, G.W Wood and Thomas Fleming, set up the Manchester Gas Works in 1817, and four years later gas was brought to the Portico to light the outside lamps. Gas piping was laid into the building in 1827 to light the newsroom. but was not extended to other parts of the building, the fumes being considered Ahighly injurious to the books@

By the middle of the 19th century the Portico had ceased to be the city's essential meeting place. Although it continued as a Library and newsroom, financial difficulties increased. In 1920, the ground floor newsroom was let to the Bank of Athens. Since 1986, it has formed the Tetley Walker wine bar "The Bank."

David Bellhouse - Bellhouse was a founder member of the Portico. Like Harrison he was the son of a joiner but unlike Harrison he had very little formal education. He was apprenticed to his father in Leeds and later came to Manchester and founded his firm. He started by building small houses and, benefiting from the expansion of Manchester, was soon involved in bigger projects. The Portico was an important contract and needed a builder of skill and experience at a time when much more was left to his discretion than is the case today. We do not know whether Harrison or Bellhouse was responsible for the dome but faults in the design cause recurrent problems. Bellhouse was certainly held responsible for the inadequacies of the roofing and the Portico committee took him to arbitration in 1809. The estimated cost of the building was £5000 and the final total paid to Bellhouse was £6,881 5s 3d. In spite of its defects, the structure has survived to demonstrate the quality of both its architect and its builder and the Bellhouses continued to work for, and to belong to, the Portico.

David Bellhouse became one of the largest contractors in Britain. He and his son, also David, were involved in many of the public buildings in Manchester, including the Theatre Royal, the first Manchester Town Hall in King Street (1822), the Royal Manchester Institution (1825 now the City Art Gallery), the warehouses, offices and stations for the Manchester and Liverpool Railway (1830), the Chorlton Row Dispensary (1839), Borough Gaol (1848) and the Denton and Gorton Reservoirs (1850). By 1838 they owned a brick yard, an iron foundry, a steam powered saw mill, an ironware house and their own steam tug and barges. David junior was also a founding director of St. Helen's Union Plate Glass Company. David senior, on his retirement from the firm in 1822, continued as a timber merchant. His sons and grandsons continued in business until the end of the century.